In the mid-1970s, Honda needed to re-assure the one-track world who held the scepter. Not only in the field of technology, but also when it came to arousing the passions inherent in motorcycles. Thus, a six-liter six-cylinder was created, which fulfilled both, and in the language of a planned economy, it could be stated that the plan was fulfilled 200 percent.

If we were to talk about the increase in popularity, the turn of the sixties and seventies meant a harvest for Honda. In 1968 came the CB750, in the early 1970s the 250 Elsinore caught all motocross riders by surprise, shortly after the first liter boxer GL1000 and it seemed that the reservoir of ideas was bottomless. But what seems is just a dream and the truth was that the internal list of improvers had already been properly crossed out. Meanwhile, Kawasaki hit back with the 900 Z1, Yamaha took the barricade by attacking from the other side with the RD350 two-stroke, and to make matters worse, Suzuki came with the GS750. A short time ago, the groundbreaking CB suddenly reeked of mediocrity. And even when the predecessor of the Gold Wing appeared in the world, it could not change the battle for the king of superbikes with its car-like travel design. The situation was well understood by the settlers on the top floors of the factory, and at one of the meetings Soichiro Honda himself and Tadashi Kume, president of the motorcycle division, agreed that only Shoichiro Irimajiri could help here. He was on the one hand the head of the development of the brand, but above all he already had a partial reputation as a legend in Honda. In 1963, he graduated from the University of Tokyo with a diploma in aeronautical engineering, and he planned to apply the acquired qualities in that field. But hey, there wasn’t a vacancy for him in the industry at the time.

So he asked at Honda, where they took him on the fly and soon the development of factory specials for Grand Prix fell into his lap. Since he didn’t have much experience, he thought theoretically and realized that he would extract more power from two cylinders than from one, from four more than from two, from five more than from four and so on. Soon, several incredible specials appeared on the racing tracks, for example the RC115 fifty-cubic two-cylinder with four-valve technology, which turned over twenty thousand. Or the five-cylinder RC148 and RC149, but especially the incredible soaked six-cylinder RC165 as a two-hundred-and-fifty with four-valve technology and the ability to turn fifteen thousand.

So if anyone at Honda had a head full of ideas suitable for the next breakthrough in the battle for the king of the one track, it was “Iri”. During the seventies, he and his team came up with the transversely mounted two-cylinder CX, a significantly modernized CB750 with a two-cam distribution, and a new queen of motorcycles was also planned. But so far without further clarification. Of course, there was an opportunity to prepare a series version of the special RCB1000, with which Honda participated in the series of endurance races. But it was a four-cylinder, Iri was afraid that people would see the bike as an attempt to catch up with Kawasaki rather than the arrival of a new superstar. The team therefore delved into concepts from the days when Shoichiro was developing Grand Prix specials. Soon, during the discussions, the six-cylinder two hundred and fifty RC165 came to the fore, the number of cylinders seemed to be in order to dazzle the public, and a project with the code name 422 was created in the development center in Asaka. It soon received the green light from the factory management, which surprisingly also suggested the simultaneous development of a liter four cylinders. With the fact that a decision will be made between them only in the prototype phase and the one that drives better will go into production. In development, two teams worked side by side, one on the four-cylinder, the other on the six-cylinder, with Minoru Morioka and Yoshitaka Omori in charge of the design. Their initial designs ran the gamut of different styles, from a classic bike that looked a lot like the CB750 to a study where if it wasn’t for the bike you’d think you were seeing a jet. Over the course of a few months, the shapes began to crystallize into the final form with the fully exposed engine clearly dominating the entire machine.

In the beginning, lower frame tubes appeared on some drawings and first mock-ups, which were supposed to bring additional strength to the entire chassis, but in the end they did not make it into production. “Mr. Honda wanted the most powerful engine possible, but at the same time he placed a lot of importance on how the engine looks,” shared Morioka of the real reason that sealed the fate of the downtubes. In addition, their presence complicated the routing of the exhaust ducts, which would not be possible to make all the same. “The exhaust manifolds would have to be bent differently, and their routing would be complicated and spoil the planned overall look, so that was another reason why we finally decided to mount the engine only at the top and at the back,” adds colleague Omori. The development of the six-cylinder took place all at once, and the fact that two adepts were developing at the same time motivated the individual teams to a high pace. Iri’s crew had the advantage of experience with the RC165, so they already knew what snags they might encounter and how to solve them, and early 1977 saw the world’s first final shapes.

But the whole bunch didn’t seem like something about them, until Omori hit the nail on the head: “There was some detail missing that would have been really great.” In the end, I came up with the idea of making a rear plastic with a small wing, and the racing department confirmed that it could work. When I called Mr. Morioki to approve my proposal, it turned out that he was working on the same element, only for the CB750F model.” Nothing prevented the construction of the first prototypes, and the biggest problem with the six-cylinder was the weight. The situation was slightly improved by the replacement of some parts with aluminum ones, such as the fork beams or the handlebars, but even so, the six-cylinder with full confidence still had three meters. On the contrary, the four-cylinder being prepared at the same time was a feather against it, as Iri himself remembers: “The four-cylinder was actually faster in track tests, but the six-cylinder provided a greater sense of excitement during acceleration, the sound of the exhaust was incomparable, as well as the smooth running of the engine.” It was just a very sexy bike.”

So it was clear which way would win, but even the four-cylinder didn’t come short, and the CB900F was created on its basis. However, the subsequent completion of the development was not a cakewalk, as significant problems in the field of handling, caused by the combination of weight and stiffness of the frame, became apparent. At first, everything seemed fine, but when the factory invited sharp riders from America to the Suzuka circuit for tests, it was no longer an illusion. “The test riders from Japan were lighter and didn’t have the problem, but the tests where the Americans were riding the bikes opened our eyes. Until then, the main point of interest for us was the engines, we knew how to make them, but the frames were not that important for us until then,” recalls Iri about the collision with reality and adds that it was one of the moments from which Honda started to fight engine and frame development more comprehensively.

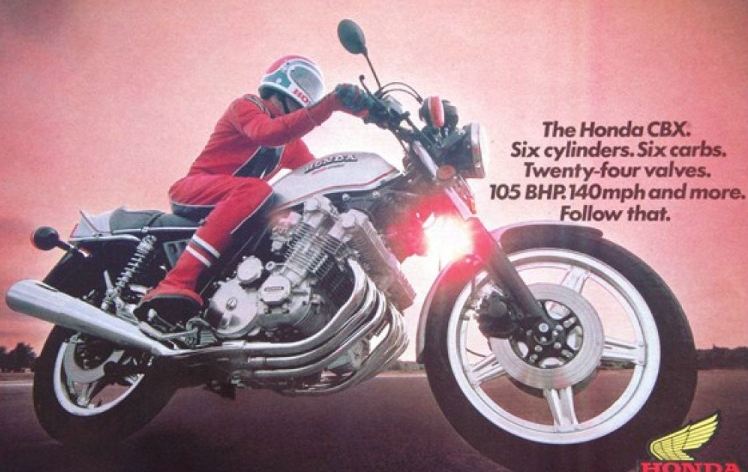

At the end of 1977, the first pre-production series was ready and the individual pieces awaited either photography for promotional materials, presentations for dealers or the first press tests. In November, the first official presentation took place at the Suzuka circuit, which was Honda’s home ground at the time. One of the specimens subsequently made its way to California, where it appeared in an exclusive test in the February 1978 issue of Cycle magazine. Editor Cook Neilson was blown away by the performance: “The CBX packs the punch Honda wanted in the motorcycle market. The bike is more than fast, it’s magical.” After a few years of the former CB750 queen being overshadowed by the 9000 Kawasaki Z1, Honda has once again taken the throne in a way that has taken the game to the next level. Most other tests similarly saw success for the six-cylinder, but in terms of sales, it was not as successful as the factory had hoped. “People were curious and interested in the bike, but they generally perceived the CBX as a machine that was big, expensive and complicated. Those who owned it fell in love with it, but overall the bike didn’t connect with the end customer enough to break sales records,” recalls Bob Troxel, a Kansas dealer at the time.

In its original form, the CBX existed for two years, after which a minor modernization followed. The performance was slightly reduced from the original one hundred and five to 98 due to sales to the states with a limit of one hundred horses, the bike received black wheels, better suspension, a larger oil cooler and a few detailed changes. But sales were still going at a tepid pace, so the six-cylinder became a sports roadster in 1981, with a central silencer at the back and a bonnet at the front. Thanks to this, the machine gained a full 24 kilograms, and even this attempt to boost sales did not work. It’s hard to say why more of them weren’t sold, but on the other hand, it was a showcase for the factory, which with the six-cylinder wanted to regain its lost position as the king of motorcycles. She then used the regained name in the shop as an advertisement for other models in the form of the CB900/1100F or a whole range of new V4s. However, in order not to be overly wise, we can again take Cook Neilson’s opinion from Cycle magazine. He summarized the CBX message as follows: “The six-cylinder exceeded the willingness of customers to accept just a certain amount of complexity and weight, and anyone with a pragmatic mind had a problem with that. But the bike was not for pragmatic bikers, it was developed for people with passion and for people with a weakness for mechanics. Perhaps it could not even be a mass issue, but on the contrary, it was included among the motorcycles, of which there are not many, but they are so special that they will never be forgotten.”